[This bust represents Alcibiades, a key figure in the play. Plutarch included a biography of Alcibiades in his Lives,which also mentions Timon in a brief incident. Alcibiades appears in Plato’s Symposium as a highly favored student of Socrates. He was a gifted politician and a superb orator, whose ambition drove him to disastrous military ventures and opposition to Athens.]

[The BBC production features Jonathan Pryce in an interpretation that emphasizes Timon’s idealism and innocence. At the feast, as his guests gorge themselves, Timon’s plate remains empty. His joy rests purely in cultivating friendship and the delight he derives from gift-giving, with no thought of benefits for himself.]

[Herman Melville (1819-1891) was a master of indirection, hiding messages in his stories and placing the reader in uncomfortable relations to his fictions. His comment on Timon of Athens unlocks a powerful second level of satire.]

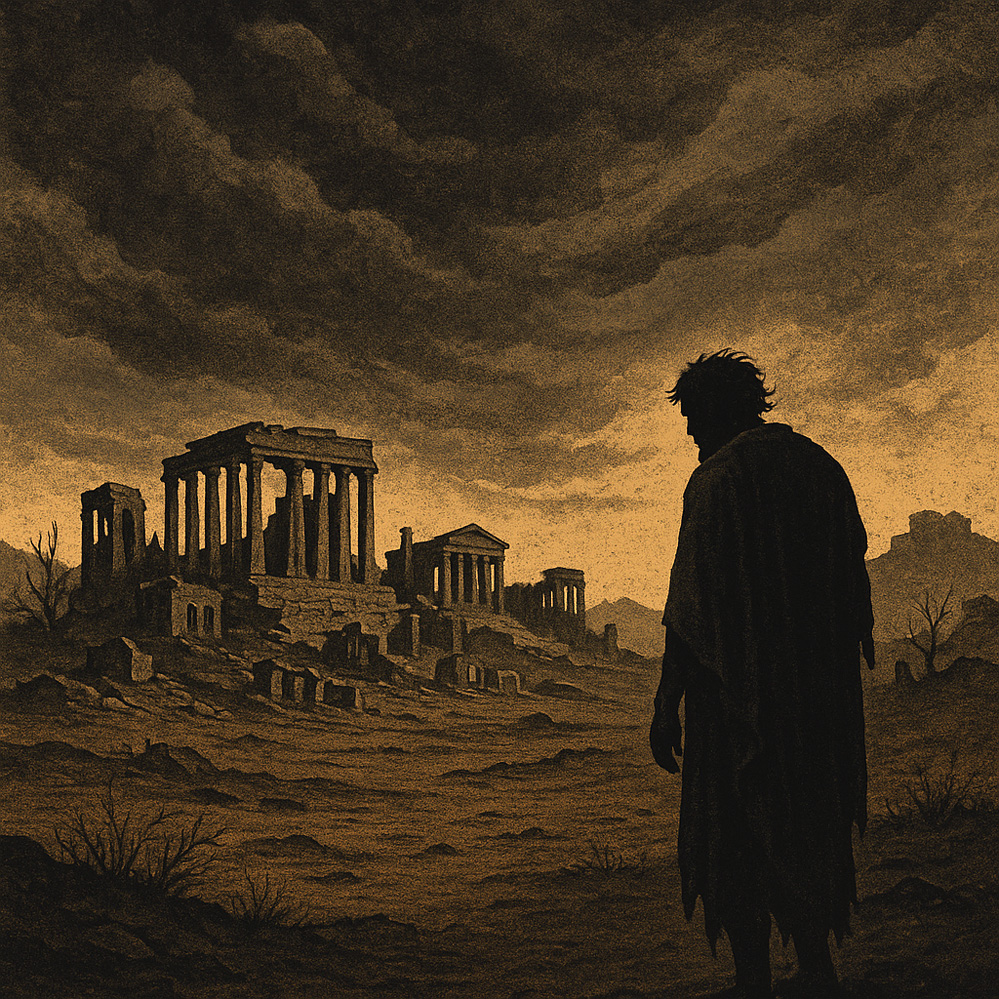

[Joseph Ziegler is Timon in a modernized version of the play. His Timon is a corporate leader for whom gift-giving is an investment bolstering his pride and

prominence. Ziegler is robust in the role. His appearance as a homeless derelict in the wasteland is shocking, and his anger is a bellow, not a whimper.]

Kathryn Hunter is Lady Timon in this recent RSC production. The gendering is bold, given the almost complete absence of women in the text. The hostess Lady Timon seeks sociability rather than power or a transcendent ideal. Her wit and high spirits take the wasteland scenes in a remarkably energetic direction.]

[The Royal Shakespeare Company production resolves the problem of the play’s ending with this stylized “Pieta". It’s a pronounced departure from the text but an emotionally effective conclusion for a Timon who has become our friend.]